Originally produced on March 27, 2017 for Mauldin Economics, LLC

By George Friedman, Xander Snyder and Cheyenne Ligon

Much has been made in the mainstream media over China’s ongoing military buildup on reefs in the South China Sea. Chinese action has thus far been largely contained to two island groups: the Spratly Islands and the Paracel Islands.

Though China has indeed been building extensively on these island groups—constructing harbors, runways, helipads, and radar facilities, and installing missile defense systems—these facilities are defensive in nature. They are meant to extend China’s reach further past its coastline.

Not all islands are developed to the same degree, and different island chains serve different strategic purposes. Additional attention has been given to Scarborough Shoal, which while not currently developed, has become a point of tension between the Philippines and China.

9-Dash Line

China’s extensive claims in the South China Sea (which form the basis for the ongoing territorial conflict between China and its neighbors) are based on the Chinese nine-dash line. Beijing uses the nine-dash line to claim sovereignty over approximately 90% of the contested waters in the South China Sea… territory extending as far as 1,243 miles away from the Chinese mainland.

China argues that the nine-dash line represents historical maritime agreements, but all involved (except China) have disputed this. When probed, China has been evasive about the actual details of purported agreements.

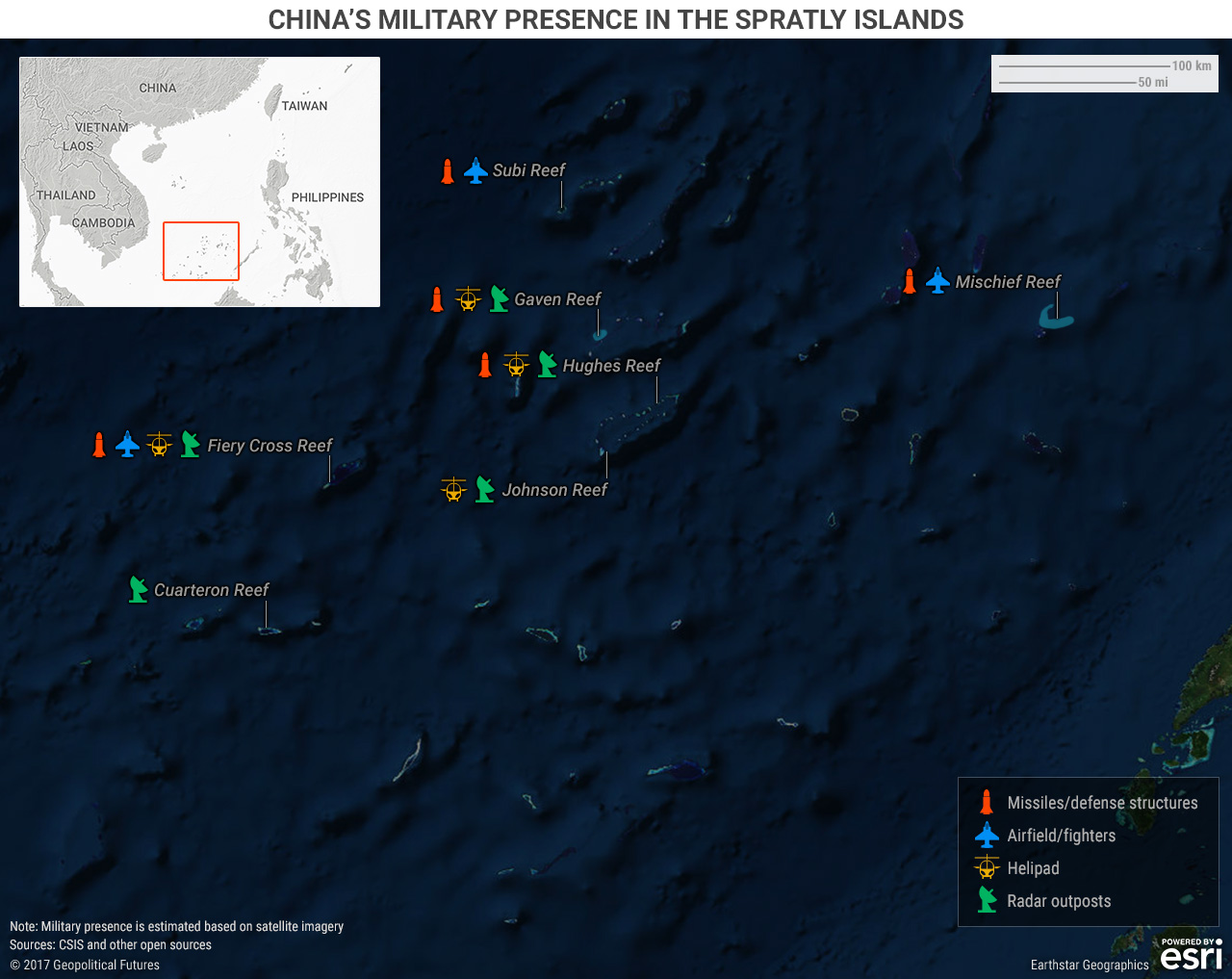

Spratly Islands

China has reclaimed extensive territory in the Spratly Islands. A 2016 report from the Pentagon estimates that China had built approximately 3,200 acres of artificial reefs in the island chain by the end of 2015, when it pledged to stop adding additional territory. This number dwarfs the mere 50 acres built by all other countries involved in the dispute during the same period.

Though the Spratly Islands contain many reefs, China’s interests are concentrated on seven. The three large reefs—Mischief, Subi, and Fiery Cross—are similar in that they all have large anti-aircraft guns and close-in weapons systems. Each features helipads, long runways, and hangars capable of holding up to 24 fighter jets and several larger planes, including the largest in the Chinese fleet.

Fiery Cross Reef is confirmed to have a harbor at which China’s largest naval vessels can dock. It has also been reported that construction of similar harbors is ongoing at Mischief and Subi reefs.

Fiery Cross, on which 200 troops are garrisoned, features recreational facilities and permanent outpost structures. Each of the three large reefs also contains four unidentified hexagonal structures, which are oriented toward the sea, and whose purpose remains unknown.

The four smaller reefs—Gaven, Hughes, Johnson, and Cuarteron—each contain structures thought to be radar towers and helipads (according to Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, a program by the Center for International and Strategic Studies focused on tracking development in the South China Sea). Additional structures, such as lighthouses, bunkers, or small supply platforms, are featured on some of these reefs but are not common to all.

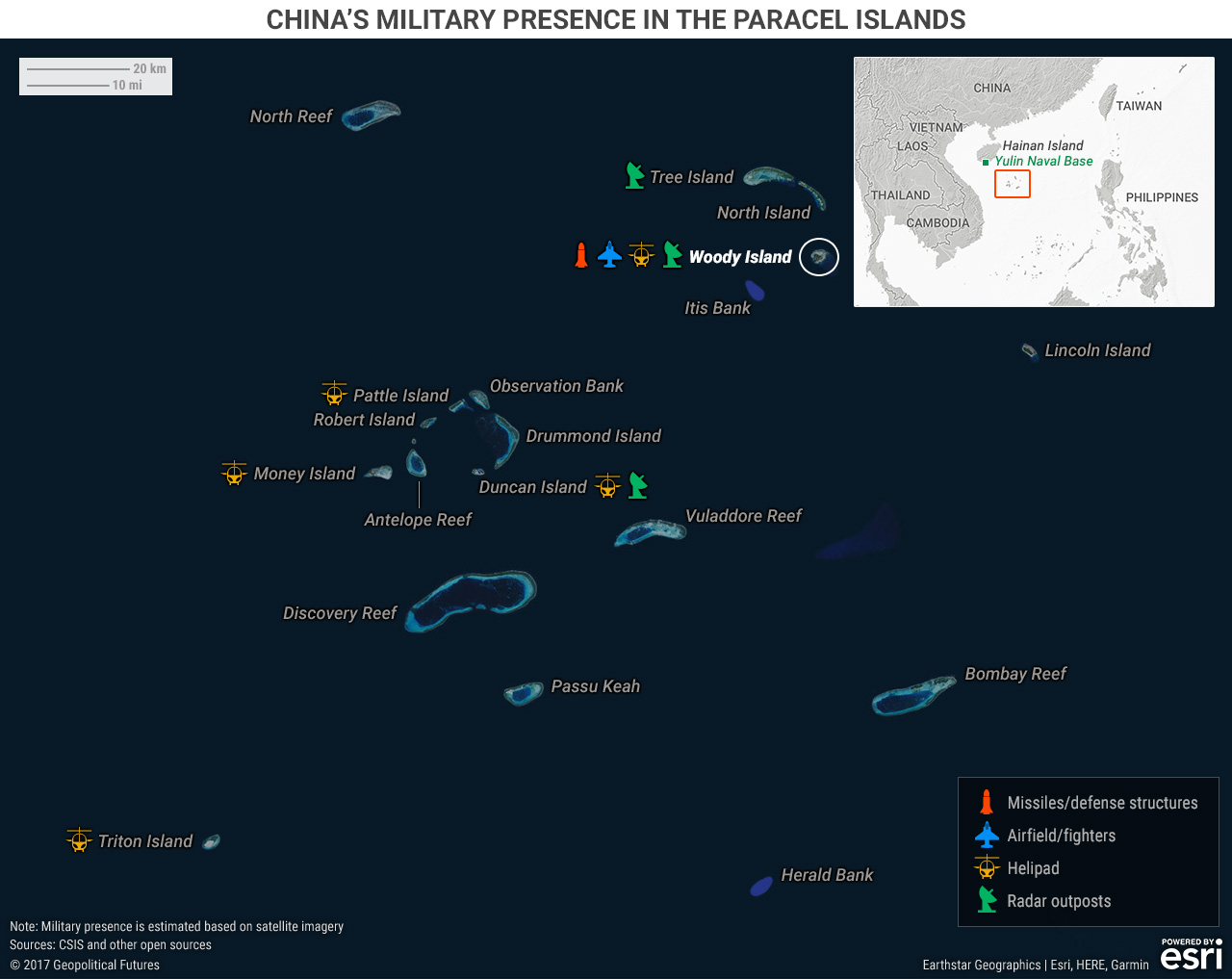

Paracel Islands

The Paracel Islands provide the Chinese with a defensive outpost approximately 200 miles southeast of the southern tip of Hainan Island, where China maintains a nuclear submarine base. Eight of the islands currently have some form of Chinese presence, with six containing at least radar capabilities.

Woody Island, located in the northeast of the island chain, has perhaps the largest presence of Chinese military in the South China Sea. In addition to 1,400 military personnel, it also has an airstrip that can support J-11 and Xian JH-7 fighter jets, up to 20 aircraft hangars, helipads, radar facilities, and a battery of HQ-9 surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) with a range of 124 miles. Despite claims in mid-2016 that these missiles were removed, recent satellite photography indicates they are still there.

Woody Island has been designated the official administrative capital of the region containing the island chains that China claims as its territory (Paracel, Spratly, and the area encompassing Scarborough Shoal).

In late 2016, the Chinese government attempted to further normalize its presence on Woody Island with daily chartered civilian flights to the island. Putting civilians on the island bolsters China’s sovereignty claim. It also increases the risk of civilian injuries in the event of an attack and, therefore, has a deterrent effect.

The other islands in the Paracels that the Chinese have occupied do not have runways, and therefore should be seen as support positions for Woody Island. While some land reclamation has begun on North and Middle islands in the East Paracels, only Tree Island, which sits just to the northeast of Woody Island, currently has any military installations. These include radar capabilities and more unidentified buried hexagonal structures. In the West Paracels, Money Island, Triton Island, Pattle Island, and Duncan Island have a combination of helicopter pads and radar.

Scarborough Shoal

While it currently has no military installations, Scarborough Shoal has been a point of tension in Philippine-Chinese relations. Looking at the above map, you can see why: Scarborough Shoal is located off the Philippines’s west coast, only 220 miles from Manila. Throughout Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s ongoing pivot between the US and China, Scarborough Shoal has remained the line Duterte has maintained that China must not cross.

Scarborough Shoal was in the headlines earlier this month as Xiao Jie (the Chinese mayor who administers the South China Sea islands) announced plans to install “environmental monitoring stations” there. This set off a chain of reactions in the Philippines as people demanded Duterte respond to what they considered Chinese aggression. Duterte stated, “What do you want me to do? Declare war against China? I can’t. We will lose all our military and policemen tomorrow and we [will be] a destroyed nation.”

The next day, the Chinese Foreign Ministry denied that China had intentions of building anything—including an environmental facility—on Scarborough Shoal, and a correction was issued to remove Xiao’s comments regarding Scarborough Shoal construction from the Hanan Daily, a state-backed newspaper. Duterte responded to China’s revised position by claiming that he doesn’t believe China would build on the shoal “out of respect for our friendship.”

Conclusion

Diplomatic spats between China and the other claimants in the South China Sea are, for now, just that—spats. China is building up military capabilities on the contested reefs, but the installations are primarily for defensive purposes.

The SAMs China installed on the reefs are mainly air area denial tools with a limited range of 124 miles, meant to shoot down incoming enemy planes. China’s planes spotted at these South China Sea installations have also been largely defensive (such as the J-11 fighter jet, which is used to maintain air superiority over the islands). The position of the reefs is also defensive: The location of the Paracel Islands gives China the ability to block Taiwanese or Philippine access to its Hainan submarine base.

However, it is possible that Chinese involvement on these reefs could progress from a defensive nature to a more offensive one. The occasional presence of Xian JH-7 fighter bombers and the construction of large harbors that can accommodate the largest ships in the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s fleet indicate China’s interest in demonstrating that it could, if provoked, carry out future attacks from these islands.

Additionally, if Scarborough Shoal becomes another base of Chinese operations, it sits close enough to the Philippines to pose an offensive threat, regardless of whether China considers it a defensive position. For now, like all Chinese moves in the South China Sea, it is just a bluff meant to make China look bigger and scarier than it actually is.

The Geopolitics of the American President

The Geopolitics of the American President