By Xander Snyder

The fact that China is facing a potential debt crisis isn’t exactly a tightly kept secret. Its debt-to-GDP ratio at the end of 2016 was roughly 260 percent; the Institute of International Finance estimated this figure was closer to 300 percent as of mid-2017. But now, even Chinese officials are acknowledging the problem and taking steps to address it – a notable change considering that the government is reluctant to admit any weaknesses in the Chinese economy.

Last week, the People’s Bank of China announced in its third-quarter review of monetary policy a slew of new regulations for China’s shadow banking industry. Shadow banking involves financial products – also called off-balance-sheet assets – that are offered by nonbank financial institutions. China’s attempt to rein in the shadow banking industry is intricately related to the real estate industry, an industry that plays a significant role in the Chinese economy. Credit rating agency Moody’s estimated in March that 25-30 percent of China’s gross domestic product is linked to the property and construction sectors. A rapid decline in real estate prices can affect the broader economy and, in turn, can lead to widespread public discontent that could threaten the central government.

A man works at a construction site of a residential skyscraper in Shanghai on Nov. 29, 2016. JOHANNES EISELE/AFP/Getty Images

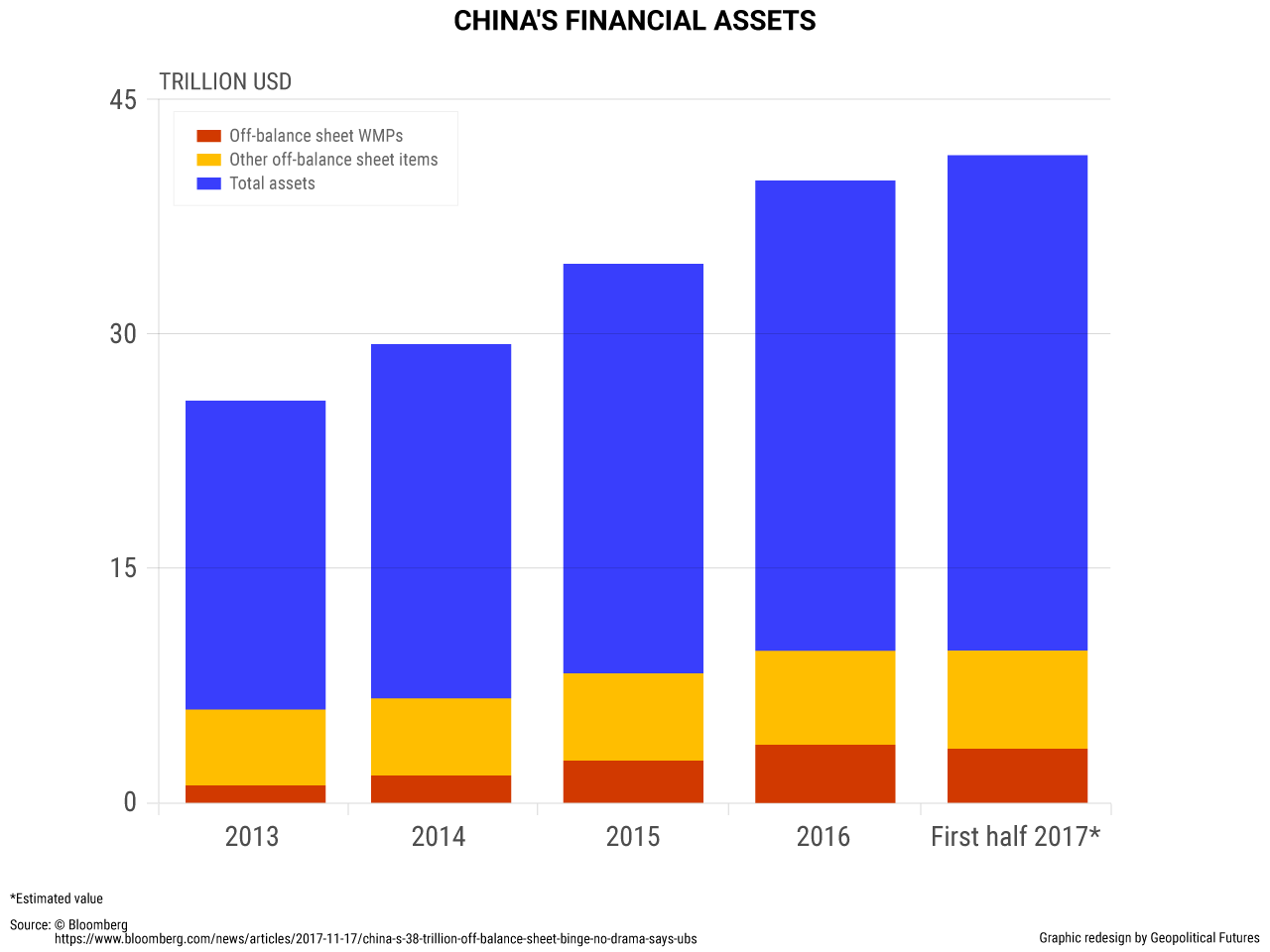

A Difficult Task

The off-balance-sheet assets that are perhaps most closely tied to real estate are called wealth management products. These are pools of capital that promise higher returns than bank deposits. Higher returns are often achieved by investing in riskier projects, such as real estate development. Estimates vary, but WMPs in China are valued at roughly $4 trillion to $5 trillion. WMPs are often managed by trusts, which are sometimes owned by bank subsidiaries. But even then, the products are not directly owned by the banks and are therefore not reported by the banks. This means that trusts managing WMPs have far more lenient reserve requirements. Other types of off-balance-sheet assets include direct loans from one company to another, facilitated by banks. It’s estimated that shadow banking assets account for roughly a third of China’s total banking system – worth $38 trillion in assets.

China’s reforms targeting off-balance-sheet items stem from the fear that a sluggish real estate market could cause widespread economic stagnation or even a financial crisis. The challenge, however, is that limiting the funds available to the real estate industry can also lead to a crisis. China’s difficult task, then, is to decrease the amount of off-balance-sheet debt while preventing a downturn in real estate that could threaten the economy.

Many of the reforms are purely financial, such as forcing trusts that manage off-balance-sheet items to hold reserves, as is required of banks. But perhaps the most important reform is an end to “implicit guarantees” that suggest that, in the event of an off-balance-sheet asset collapse, the central government will foot the bill and protect WMP investments.

These implicit guarantees stem from the notion that WMPs are deposit-like vehicles. Bank deposits come with an explicit guarantee that if a bank is unable to pay its debts, deposits will be protected. Bank deposits are therefore considered very safe. WMPs carry no such guarantee, but they were initially marketed to imply that they did. Though most Chinese investors today realize that WMPs have no guarantees, they do believe that the government would prevent a collapse of the WMP market with a bailout, and that WMPs are therefore just as safe as depositing money in a bank while offering higher returns.

Who Will Take the Hit?

Of course, higher returns almost never come without higher risk. But the assumption that WMPs carried no risk is partly responsible for their rapid growth over the past decade. Beijing is now trying to force investors to realize that there is real risk in these investments, and that in the event of a run on WMP products or a rapid decline in real estate prices that causes defaults on their investments, they will in fact lose money.

But many investors still don’t believe that the government would let the market collapse. Interviews with Chinese investors published by media outlets over the past several days indicate that many still believe WMPs carry minimal risk, despite the recent changes. The only thing that might convince them otherwise is if WMPs were allowed to fail and investors lost their investments.

This presents another problem: If WMPs fail, which investors would take the losses? Would the losses be spread equally, or would the government target certain entities?

As noted in a paper published by New York University, Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance, and Tsinghua School of Economics and Management, small and medium-sized banks have been responsible for much of the growth in WMPs since 2008. These banks are not as systemically important as China’s four large state-owned banks. Thus, it will be the WMPs offered by small and medium-sized banks that Beijing will have to let fail, because a default at one of these banks is less likely to lead to a crisis. But Beijing must also maintain confidence in the system at the same time to avoid a run on WMP assets, which would severely cripple the real estate industry. Many WMPs are short-term securities that fund long-term projects, meaning that investors have the option to pull their money out of the WMPs before the projects are completed. If investors recognize that WMPs are not guaranteed, the risk is even greater that they could decide not to reinvest in them, and this would leave real estate projects in limbo and possibly drive developers into default. This is what Beijing is trying to avoid.

The new reforms are different in both scale and scope from previous government attempts to rein in the sector. By coming into force at the same time, these regulations will have a greater impact than the other, smaller changes the government imposed incrementally. Since the Chinese Party Congress in October, the government has felt more comfortable making drastic changes to the economy. Prior to the congress, the central bank dodged the issue.

But President Xi Jinping has made it clear that China is entering a new era and that now is the time for grander reforms. The central bank’s announcement makes clear Xi’s intent. But it remains to be seen whether the government will actually be able to enforce the new regulations and whether it can implement these changes without causing the very housing collapse that it is so desperately trying to avoid.

The Geopolitics of the American President

The Geopolitics of the American President